The apparent victory of Prabowo Subianto in Indonesia’s presidential election is a dramatic moment in the country’s history.

Even though polls put him as the front-runner for many weeks before polling day, the margin by which he beat his two opponents, according to the usually accurate early vote counts, was much higher than expected.

They all project he will be comfortably over the 50% threshold needed to win outright in the first round.

The final count still needs to be officially confirmed, but most Indonesians will now accept that the next five years will be under a President Prabowo.

So what happens now?

The transition from one administration to another is a slow one in Indonesia. It will take the Election Commission up to a month to confirm the results.

The inauguration of the new president does not take place until October. There will be many months of intense negotiations to decide what kind of government Mr Prabowo will form.

And while his win in the presidential race appears to be an emphatic one, Mr Prabowo’s party, Gerindra, is currently projected to win only around 13% of the seats in parliament.

He will need to persuade other parties to back him in order to have a working majority in parliament to get laws passed, which means offering inducements in the form of cabinet positions. Some of those parties supported rival presidential candidates.

A new kind of president

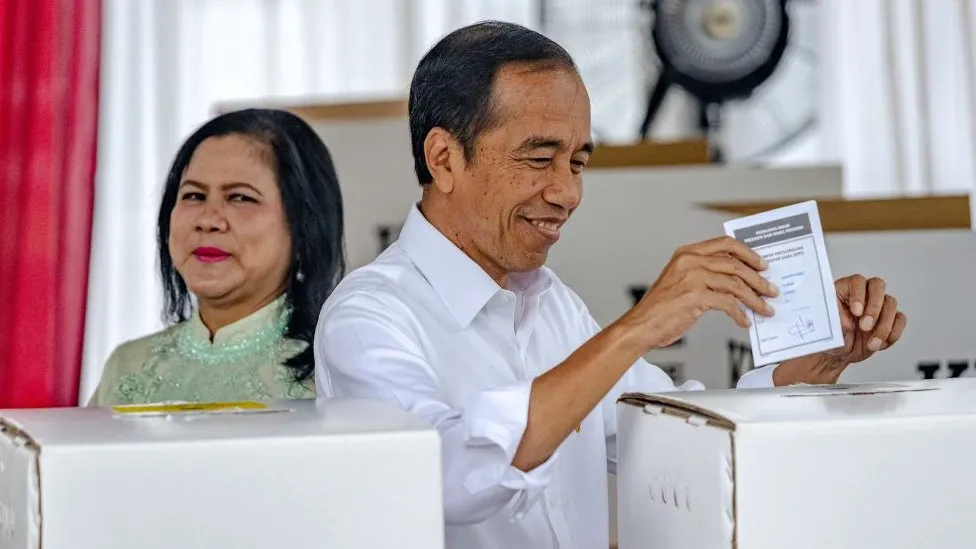

Outgoing President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo was a master of coalition politics, co-opting his opponents so that in his last term of office, he was backed by more than 80% of MPs.

This smoothed away political conflict and allowed him to push through his ambitious infrastructure projects, but it also created what some have called “opposition-less politics”, where no-one challenged the government’s agenda.

Will Mr Prabowo, a less compliant leader, try the same “big tent” approach to governing?

And what kind of relationship will he have with Megawati Sukarnoputri, the grande dame of Indonesian politics and leader of the largest party, the PDIP?

The PDIP was President Jokowi’s main parliamentary sponsor during his 10 years in office, and was shocked by his switch to the Prabowo camp last year, causing a lot of ill-feeling. A lot depends on whether Ms Megawati is ready to be in opposition, whether she can be induced to bury the hatchet and join the ruling coalition, and whether Mr Prabowo wants that.

There are questions too over the future relationship between Mr Prabowo and President Jokowi.

Mr Jokowi still enjoys enviable popularity ratings, and his support played a critical part in the success of the Prabowo campaign, bringing over huge numbers of voters who might otherwise have backed Ganjar Pranowo, the PDIP candidate.

In return his son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, was made Mr Prabowo’s running mate, though only after a much-criticised court ruling exempted him from the constitutionally-mandated age threshold. If something were to incapacitate Mr Prabowo, who, at 72 years-old is in uncertain health, the inexperienced Gibran would succeed him and might be expected to rely on his father’s help.

However President Jokowi need only look next door, at the Philippines, to see how such a Faustian arrangement can fall apart.

In its 2022 election, the campaign of Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr also relied heavily on the support of a popular incumbent, President Rodrigo Duterte, to win the presidency.

Mr Marcos too agreed to take Mr Duterte’s daughter Sara as his running mate. Two years on, the once-allied families have fallen out badly, and Mr Duterte has discovered that as a former president, he has little influence. Now that he has the prize of the presidency, Mr Prabowo might also discover he no longer needs his predecessor’s support.

Indonesians will need to adjust themselves to a very different style of leadership.

Mr Prabowo’s personality is unlike that of President Jokowi in almost every way, except perhaps their Machiavellian understanding of political power.

Where the president is famously soft-spoken and conciliatory, Mr Prabowo has a reputation for ill-tempered outbursts and abrasive opinions. He takes pride in the long career he had as an officer in the Indonesian special forces, despite allegations of serious human rights abuses made against both him and the unit in the past.

Many Indonesians view a Prabowo presidency with real alarm.

“His impulse, his instinct, is to be xenophobic, to be an authoritarian leader. I’m afraid he doesn’t change – his character doesn’t change”, says Andreas Harsono at Human Rights Watch.

However, during the campaign he transformed his public image into that of a quirky grandfatherly figure.

At the age of 72, he is less steady on his feet and has often been visibly tired at campaign rallies. Some say he has really changed, in his desire to win the top job.

It is also worth remembering just how long Mr Prabowo has sought the presidency – starting his first bid in 2004, and how strategically he rebuilt his reputation after being sacked from the army and forced into exile in 1998. He has shown patience and guile in his path to power.

He has repeatedly promised to continue his predecessor’s development and infrastructure-focussed policies, portraying himself more as the heir to a long line of Indonesian presidents, than a radical departure.

Source: BBC