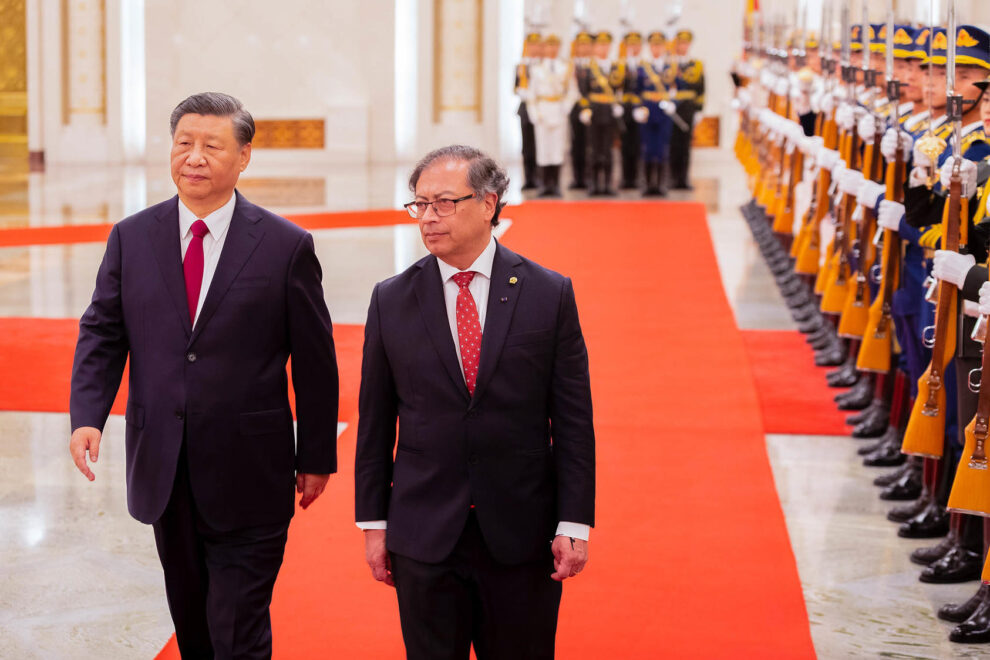

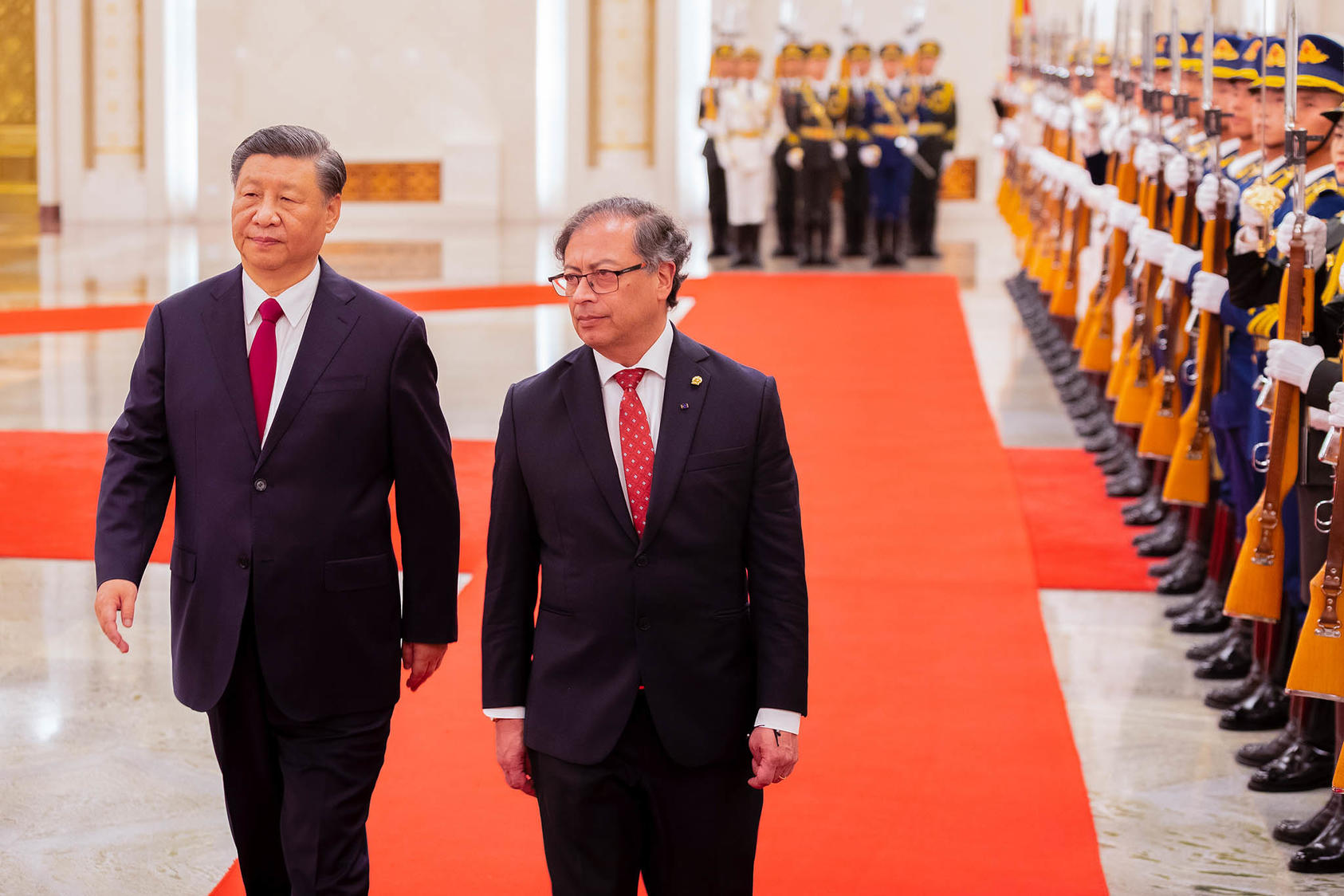

In Beijing, Petro and Xi seek to expand relationship, upgrade ties to a ‘strategic partnership.’

Colombian President Gustavo Petro’s visit to Beijing in October amounted to a notable — if quite small — step forward for China and Colombia, building on growing trade and other ties, while also laying the groundwork for cooperation on issues, such as media and security, which China has promoted across the region.

Colombia remains among the countries in Latin America that have been slower to embrace China as a major partner, whether in economic terms or on issues of political interest. This is due in some part to the long-standing U.S.-Colombia partnership, which continues to bear fruit despite policy differences between the Biden and Petro governments. The United States is Colombia’s largest export partner and a top donor, having provided over $677 million in assistance in 2022. This included extensive support for the Colombian government’s counternarcotics strategy and the continued implementation of its peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

U.S.-Colombia relations no doubt loomed over the Xi-Petro exchange last month, prompting some degree of restraint. But Colombia-China plans aren’t clearly on the fast track in any case — especially as China’s deals there encounter ongoing obstacles, and as the Petro government struggles to advance its myriad domestic policy objectives.

A Restrained Relationship

Colombia has for many years approached Beijing with a greater degree of caution than many of its neighbors, whether due to its historical ties to the United States or simply a greater, comparative preference for engaging with South American, North American and European companies. Chinese tech, infrastructure and other firms have been on the ground in Colombia since the early 2000s, but with little to show for their efforts until 2019, when China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) was awarded the rights to build the Mar 2 project, a 254 kilometer toll road running from Cañasgordas to Necoclí in Colombia’s Antioquia region — a deal approved by the administration of Colombia’s then pro-U.S. president Iván Duque. Chinese Embassy commercial representatives lobbied hard for a role in Colombia’s Fourth Generation Roads Concession Program (4G), of which Mar 2 is a part, as early as 2015, offering China Development Bank financial support for the project.

China also sought to strengthen bilateral ties during the late premier Li Keqiang’s 2015 visit to Bogotá, again during the term of another pro-U.S. president, Juan Manuel Santos. Li proposed a bilateral free trade agreement with Colombia (following South Korea and Japan’s lead), in addition to more cooperation in several specific economic sectors, including infrastructure development related to and surrounding the Buenaventura port. A proposed “dry channel” project, linking Buenaventura with Barranquilla by rail, was in discussion then, for instance. There was limited political support for a free trade agreement with China at the time, however, and plans for a possible dry channel and a separate Magdalena River dredging deal dried up.

Colombia also continues to be among the region’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) holdouts, alongside a handful of other countries, such as Brazil, Mexico and Taiwan’s remaining allies in the region. As mayor of Bogotá and now president of the republic, Petro has expressed interest in working with China on major infrastructure development, but he stopped short of signing a Belt and Road Cooperation Agreement while in China, instead noting that “Colombia is ready to synergize its geographical advantage and its development strategies with the BRI,” while also signaling future cooperating in priority BRI sectors, such as infrastructure and clean energy.

Key Deliverables from the Petro-Xi Meeting

Still, as evident in the deliverables from the Petro-Xi meeting (see Table 1), Chinese engagement with Colombia is progressing, if at its own pace. The heads of state signed 12 agreements, including two that lay out the steps required to advance Colombian beef and quinoa exports to China, building on an approximately $19 billion trade relationship.

Other deals are in areas that China has prioritized across the region as it looks to export a wider range of high-tech goods and services. A third of the 12 agreements support educational exchange in science and tech, for instance, which is being carried out by China’s ministries, companies and universities in much of Latin America — to advance host-country development objectives, but also China’s interest in technological standards-setting and tech sales across the Global South, as well as an ongoing effort to boost China’s competitiveness in the field of international education. Agreement 10 relatedly encourages China’s National Data Administration to cooperate with Colombia’s Ministry of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) on issues related to the digital economy.

Agreement 12 promotes the “exchange and cooperation between the public media of the two countries,” as signed by Colombia’s minister of ICT, Mauricio Lizcano, and the vice president of China Media Group, Xing Bo. This is another area in Latin America and other regions where China is exceedingly active at present. China’s media services have been remarkably successful at establishing partnerships across the region, whether at the national level or with individual media outlets. These include low-cost, content-sharing arrangements that are helpful to lower-budget and understaffed outlets, but which — as China’s state media is wont to do — also communicate Chinese government viewpoints.

Table 1. Colombia’s October 2023 Agreements with China

China and Colombia also notably upgraded their relationship to a “strategic partnership,” according to China’s classification system, bringing it on par with Bolivia and Uruguay. This is a nod to growing bilateral ties, including the possibility of cooperation in areas such as security (e.g., police force coordination) and innovation. But Colombia still ranks below its neighbors, most of which have been labeled “comprehensive strategic partner” by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

An Eye on Transportation Projects

In a joint declaration, China and Colombia also committed to promoting investment projects in transportation infrastructure at the national and regional levels, as well as sustainable urban mobility systems. This portion of the declaration is possibly related to the embattled Bogotá Metro project, which has been rather emblematic of the fits and starts in China-Colombia infrastructure cooperation. The Line 1 project is all but suspended amid bitter disagreement between Bogotá Mayor Claudia López and Petro on metro construction. Petro prefers a more expensive, below-ground option while López has sought to advance an already planned elevated rail system. Before meeting Xi on October 25, Petro reportedly held discussions with the two Chinese companies — CHEC and Xi’an Metro — involved in metro construction, suggesting that Colombia would foot the entire bill if the metro were built below the city. Lopéz responded, noting that “the decision about the city’s metro is not made in China.”

Despite the metro’s ongoing problems (which long pre-dated China’s involvement), other projects may still be in discussion, assuming any Chinese interest at the moment. Soon after being elected in 2022, Petro stressed Colombia’s interest in advancing the dry canal project, for example, though without much reference since.

A Slow and Steady Step Forward

Beyond these developments was an agreement to welcome China’s still-loosely-defined Global Security Initiative and Global Civilization Initiative, and to maintain close communication with China on issues of global concern, such as the war in the Middle East. China also applauded Petro’s efforts to restore and normalize relations between Colombia and Venezuela. China remains committed to aiding Venezuela in a limited form, while also protecting its oil interests there.

All of this activity marks a slow and steady step forward in the Colombia-China relationship, and one that would appear to meet as many (if not more) of China’s objectives as it does Colombia’s. To maximize the benefit of partnership with China, Colombia’s government will need to consider how best to engage Chinese and other companies in support of key transport and other infrastructure, while also weighing the benefits and drawbacks of cooperation with China in areas such as media, tech policy and security. At present, though, the Petro administration would appear to be consumed by a wide range of other matters, including its own “floundering” popularity.

Source : usip.org