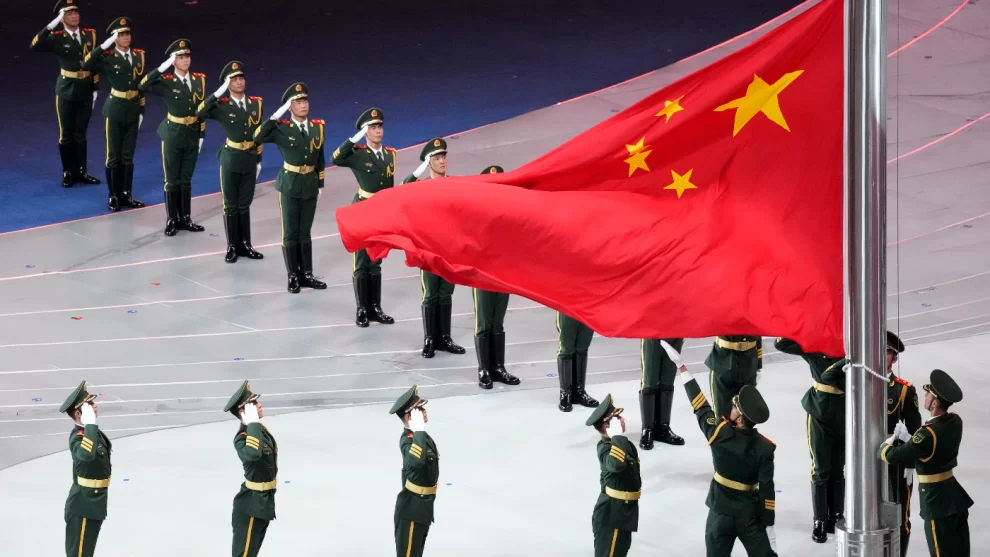

Members of Congress are embracing one of their favorite pastimes, playing war. In this case, rather than merely pontificating or passing threatening resolutions, the members of the House Select Committee on China (more formally the House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party) are continuing its obsession with war games.

Earlier this year, they simulated a 2027 Chinese invasion of Taiwan organized by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), a Washington think tank that has been running similar simulations recently.

Last month, the chair of the House Select Committee on China, Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wisc.) called the tabletop exercises a “useful way of kind of pushing people outside their intellectual comfort zone and forcing them to go beyond just the standard conversation or the standard back and forth.”

In reality, there is nothing more in Congress’s comfort zone than playing war.

As Washington descends deeper into the era of “great power competition” these sorts of war games have been a veritable cottage industry. And it’s not just the think tanks hosting them. The media and the larger pundit class have got on board as they loudly debate the finer details of what it presumes is an inevitable military conflict between the United States and China.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with war games or “tabletop exercises.” Attempting to game out how a crisis may unfold, the decision that will need to be made and the relative strengths and weaknesses of one’s preparedness are all good things with a long history in our national security planning. In fact, such exercises can be used to identify how a future crisis might inadvertently spin out of control into a conflict. Wise policymakers could, for instance, use them to identify where urgent diplomacy is needed to prevent a miscommunication from becoming a maelstrom.

The problem is that the games, no matter how well designed, are only ever highly controlled simulations of what, in reality, are highly complex situations that will play out in unexpected ways, often with unforeseen complications. In truth, our understanding of foreign actors is always limited, both by our limited visibility and also our own cultural and political biases through which we cannot help but see the world. And, in the worst case, such exercises may convince policymakers that they have to act first, resulting in escalatory spirals that make war more, not less likely.

Of course, the biggest difference between a war game and reality is that in the game, no one actually dies. In actual wars — which are fought with bullets and bombs in real, not simulated battles — real people die. And in the case of a war between the United States and China, two nuclear-armed superpowers, it may be that those deaths are measured in the billions.

And therein lies the danger with Washington’s current war game obsession. Rather than rationally preparing for contingencies in the U.S.-China relationship as it dangerously escalates, war games allow policymakers and pundits to play pretend. They let them act tough and talk about fancy weapons systems. They let them imagine winning a war and vanquishing an enemy. But they don’t force them to confront reality. They don’t force them to look into a mother’s eyes to explain why her son won’t be coming home. They don’t have to shelter as yet another airstrike threatens instantaneous death. And they don’t cause them to grapple with the almost unimaginable potential of superpowers fighting a nuclear war.

We need our policymakers not to play general but to do their actual jobs. They need to spend less time imagining war and more time talking with its would-be victims. They need to hear from the people being harmed right now, not just in some future hypothetical war, by the escalating U.S.-China conflict. And they need to grapple not with how to win a war but how to prevent one from ever happening.

The truth is, more than a century and a half after Gen. Sherman’s famous observation, war is still hell. It is not and never will be a game, and we need to stop treating it like it is.

Source : The Hill