The Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (SCS/DOC) is a failed attempt by ASEAN to stop situations from getting worse in the region, while the parties worked toward the eventual attainment of a Code of Conduct which would presumably make things better.

Most importantly, the parties agreed to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, refraining from inhabiting the islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features.

There are three separate references regarding respect for and adherence to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and other universally recognized principles of international law. They all agreed to respect the provisions of this declaration and take actions consistent therewith. Had all parties lived up to this agreement, the South China Sea would have been a less explosive region today.

The major loophole in the SCS/DOC is that it is a non-binding agreement signed by regional foreign ministers rather than an officially binding document signed by the head of the states. This gives China the upper-hand by being the biggest claimant with the largest military in the region.

Another issue is that the agreement in the SCS/DOC seeks ways of ensuring just and humane treatment of all persons who are either in danger or in distress.

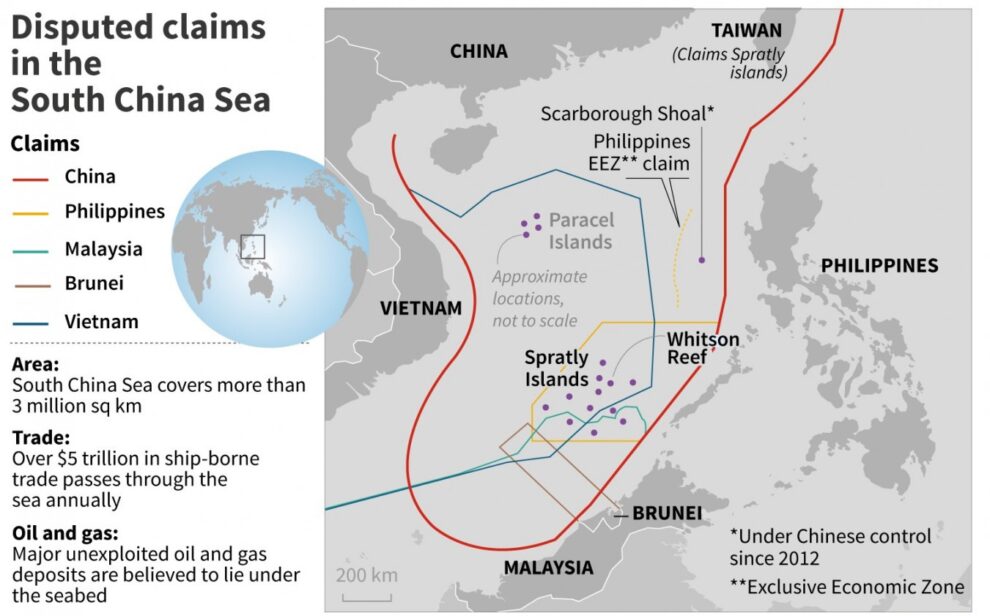

When Beijing started building its manmade islands on low tide elevation reefs, it disingenuously claimed it was building shelters for fishermen. This, of course, did not negate the fact that it ultimately violated its pledge not to inhabit uninhabited reefs. Beijing’s claims to territorial waters surrounding these manmade islands are also in clear violation of universally recognized principles of international law, including UNCLOS.

The non-binding nature of the SCS/DOC and its lack of enforcement measures have allowed all parties, including but not limited to China, to violate the letter and spirit of the agreement. However, none of the nations has been as blatant or expansive as China.

The SCS/DOC calls for regular consultations on the observance of this declaration. This appears a good point to start. Use the December 2002 signing of the SCS/DOC as the starting point and then identify all the actions taken by different parties since then that complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability. An agreement by all parties to return to the status quo circa 2002 would demonstrate their good faith in defusing and ultimately resolving tensions in the SCS.

The various ASEAN claimants would also do themselves a great favor and significantly improve ASEAN’s bargaining power if they could settle their conflicting claims and speak with one voice on which the rightful claimants are. Differences among the ASEAN claimants enhance Beijing’s ability to play divide and conquer.

All ASEAN states, and the rest of the international community, need to continually endorse and call attention to the July 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague that invalidated both China’s nine-dashed line claims in the South China Sea and the legal status of its manmade islands.

Beijing’s decision to ignore the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s binding ruling keeps tensions high and raises the risk of conflict in the SCS. China has illegally, by almost everyone’s interpretation of international law, declared 12-mile limits around their manmade islands and continually warns ships and aircraft to stay away. The US (among others), intent on flying and sailing anywhere allowed by international law refuses to obey such restrictions.

Chinese officials argue that US Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) aimed at contesting these illegal claims are the source of trouble, even though the root cause is Chinese territorial claims related to these illegal islands, which have been heavily fortified despite Chinese President Xi Jinping assuring the then US president Barrack Obama that they would not be militarized.

A disruption of shipping in the SCS could have disastrous consequences not only for the countries of Southeast Asia but globally. A frequently cited estimate says that $5.3 trillion of global trade passes through this region.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, if not reversed, also sets a dangerous precedent regarding the use of force to settle territorial disputes. China’s historical claim to the entire SCS echoes Putin’s claim that Ukraine is not a real country but part of the historic Russian empire. While all eyes are on the possibility of Chinese military action against Taiwan, SCS islands occupied by other claimants would be a soft target. Taiwan is also the most at risk given its overlapping claim with China and the increasing potential of the Chinese military. One can easily envision a scenario where a Chinese invasion of Taiwan proper begins with an action to seize Taiwan-occupied islands in the SCS.

ASEAN’s response is unknown and untested but I guess that it would bury its head in the sand and avoid involvement or even comment on what Beijing would call an internal Chinese dispute, even though the other SCS islands could be the next step, rather than Taiwan proper.

Some would argue that the Philippines is most at risk but the use of deadly force against Philippine installations or forces, even on disputed territory, would invoke the US-Philippine Defense Treaty, as Washington recently reminded Beijing. As a result, Malaysia or possibly Vietnam would be at utmost risk after Taiwan.

Before ASEAN could expect others to come to its aid, it must demonstrate a willingness and ability to defend and stand for itself. Other ASEAN claimants should follow Manila’s lead and take their cases to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague.

Rival ASEAN claimants could set an example by taking their overlapping claims to the Hague and promising to abide by the decision. Various ASEAN mechanisms could be called into play but the requirement for full consensus makes it doubtful that ASEAN as an organization will ever be willing much less able to pressure China.

A binding, enforceable code of conduct is what’s needed but, regrettably, the prospects for achieving one are close to zero.

Source : The Jakarta Post